Katie Donington is Senior Lecturer in History at the Open University. She specialises in the history of transatlantic slavery.

How did the national bank support transatlantic slavery?

As the Bank of England Museum explores its financial connections to slavery, broader questions remain about Caribbean reparations.

In August 2020 during the Black Lives Matter protests, the Bank of England announced it would remove from display 8 painting and 2 busts of former governors and director with links to slavery. It appointed a researcher to document its connections to slavery and committed to using this work to inform interpretation in the Bank of England Museum. When the Covid-19 pandemic shut the doors of the nation’s cultural organisations it gave the Museum time to prepare a new exhibition ‘Slavery & the Bank’ (April 2022 – April 2023). The exhibition explores the Bank’s involvement in the business of slavery and casts light on financial connections to the City of London more broadly.

Profit and human cost

The role of the Bank in slavery’s financial networks is represented in the main display and via additional signage across the museum. The context is carefully set out; it served the banking needs of slave traders (including monopoly trading companies like the Royal African Company), slave-owners, and West India merchants. Its provisions included accounts, overdrafts, credit, and discounting bills of exchange (cash-in payment agreements). These mechanisms were vital because Caribbean slave societies were heavily indebted owing to the capital-intensive requirements of plantation agriculture and the time it took for commodities to be grown, transported, and sold at market. The Bank played an important role in sustaining slavery’s commercial eco-system.

Governors and directors of the Bank with interests in the slave economy are featured. To achieve this position an individual had to own significant Bank stock – upwards of £4000 for a governor. Their slave-produced wealth was used for the Bank’s daily operations. Whilst the Bank has so far identified 25 individuals, the exhibition focuses on 4 case studies: Sir Robert Clayton (1629-1707), Sir Gilbert Heathcote (1652-33), William Manning (1763-1835), and Sir George Harnage (1767-1836). Disturbing details emerge in Harnage’s story; the ledger of his Barbados plantation Boarded Hall included the cost of a cage to imprison an enslaved man. Clayton’s story draws attention to the relationship between slavery and philanthropy – he was President of St. Thomas’ Hospital and contributed to its construction.

The Bank’s role in slavery compensation is detailed. When the British government abolished slavery in 1833 it paid the slave-owners £20 million in compensation. The Bank did not fund compensation, but it did help to manage the payments on behalf of the government.

The most significant finding was made by researcher Michael Bennett who was tasked with combing the Bank’s archive to look for evidence of its participation. In 2020, the Bank stated that it ‘was never itself directly involved in the slave trade’. Bennett’s work reveals that the Bank owned two sugar plantations in Grenada – Bacolet and Chemin between 1774-1791. Originally belonging to the Scottish merchant firm Alexander & Sons, the plantations were used as security to access the Bank’s service discounting bills of exchange. When the partnership went bankrupt, the Bank became the owners of both plantations and the 599 enslaved people who laboured on them.

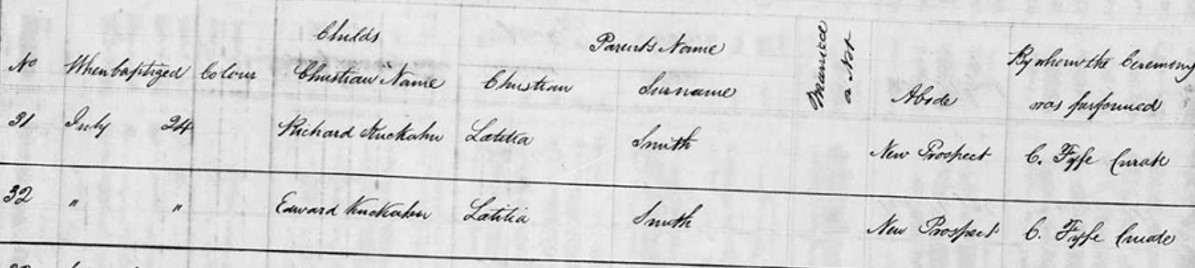

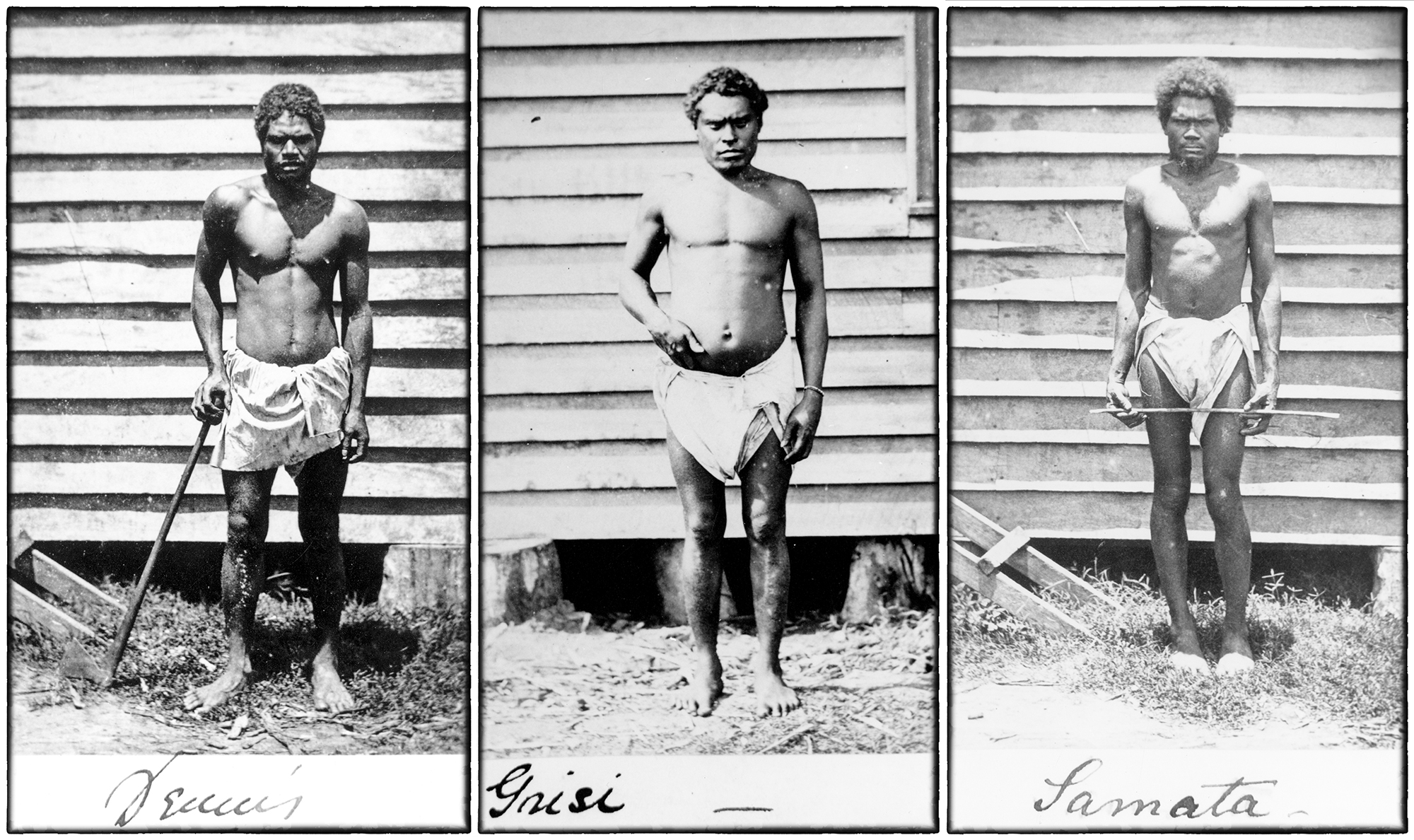

The importance of this story is reflected in its spatial position – it occupies the middle of the exhibition on a circular raised platform. The curatorial decision to make this the heart of the narrative marks an attempt to centre the enslaved within a rendering of the story that otherwise concentrates on the economics of slavery. The most powerful object on display is a facsimile of a plantation inventory from 1788. It listed different forms of ‘property’; enslaved humans were recorded alongside land, stock, and buildings. The monetary value attributed to them was inscribed next to the names they had been given. It is a chilling act of commercial bureaucracy designed to transform people into commodities. The space is surrounded overhead by a black and white banner onto which the given names of the enslaved are printed. Among this terrible accounting of enslavement two unnamed infants are remembered. The evidential fragments used to memorialise the enslaved are in stark contrast to the portraits and biographical details which document the Bank’s former governors and directors. The absence of material available on the lives of enslaved people is a reminder of the racial power imbalance of historical representation.

Opening up a dialogue about slavery and its legacies?

According to curator Liberty Paterson, creating a space for fostering dialogue was a priority for the Bank of England Ethnic Minority Network who consulted on the exhibition. Each text panel poses a question designed to open a conversation. The central space includes a display of visitor comments cards. Whilst I was there two women of Jamaican heritage were discussing reparations – something raised in the comments cards. This is a longstanding issue within the Caribbean and was highlighted by protests during the Royal Tour. There was scant acknowledgement of this debate in the exhibition – a brief mention in the section on compensation. Despite the narrative exploring the historical role of finance in supporting the system, ideas about racial capitalism were not addressed directly. Slavery and colonialism shaped a global economic system in which capital, land, property, and power were accumulated and denied along racial lines. Slave-based wealth enriched British society as investigations by universities, cultural establishments, and philanthropic organisations have demonstrated. This history also led to Caribbean underdevelopment. But where does the responsibility for reparative justice sit – with individual families, institutions, or the state? Museums can play a role in historical repair by increasing an understanding of this history and its legacies, but questions remain about how much further Britain is willing to go to address the systemic inequity, that whilst not named, the exhibition has put on display.

I am writing a book on just such an individual, Henry Redhead Yorke (1771/2-1813), a black political writer and agitator of the French Revolutionary period, little-known today. He became a revolutionary radical in 1792 but then after a spell in prison for his activities he performed a complete volte face and took up an ultra-loyalist Tory position. We know this because he published much political writing and his arrest and trial are well-documented. However, Yorke appears not to have left any personal letters, diaries or memoirs except an epistolary travelogue of a visit to France in 1802. Finding evidence of his personal life required chasing threads through a motley collection of sources with many dead ends and false leads along the way. Some of the questions this research generated illustrate the problems Hanley and Killingray identified.

I am writing a book on just such an individual, Henry Redhead Yorke (1771/2-1813), a black political writer and agitator of the French Revolutionary period, little-known today. He became a revolutionary radical in 1792 but then after a spell in prison for his activities he performed a complete volte face and took up an ultra-loyalist Tory position. We know this because he published much political writing and his arrest and trial are well-documented. However, Yorke appears not to have left any personal letters, diaries or memoirs except an epistolary travelogue of a visit to France in 1802. Finding evidence of his personal life required chasing threads through a motley collection of sources with many dead ends and false leads along the way. Some of the questions this research generated illustrate the problems Hanley and Killingray identified.

Yorke was, then, an illegitimate Creole

Yorke was, then, an illegitimate Creole

On Saturday October 24 our fourth regional workshop was held in Manchester at the Central Library – one of Manchester’s impressive Victorian buildings which has recently been refurbished and is now home to digital hubs, local history activities, meeting rooms and a café with good food as well as the usual library facilities. We had a full day of talks and discussion, organised by

On Saturday October 24 our fourth regional workshop was held in Manchester at the Central Library – one of Manchester’s impressive Victorian buildings which has recently been refurbished and is now home to digital hubs, local history activities, meeting rooms and a café with good food as well as the usual library facilities. We had a full day of talks and discussion, organised by  We were really fortunate after coffee to have the black feminist artist

We were really fortunate after coffee to have the black feminist artist  In the afternoon

In the afternoon