By Amanda Goodrich, The Open University

Recently at the What’s Happening in Black History III Conference held by the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, David Killingray and Ryan Hanley raised important issues about how we write ‘black history’ and who we study. Both suggested that we need to dig deep in the archives, and find more and different black people in order to develop a broader perspective. For example, not all black people in Britain in the late eighteenth century were formerly enslaved Africans and nor were they all focused on slavery and abolition. Hanley noted, though, that the difficulty of finding such people and the paucity of evidence about their lives presents a problem for historians. In common with the poor, women and others in the eighteenth century, black people in Britain tended to live on the fringes of society, they wrote little or nothing and anything they did write, or any record of their lives, is unlikely to have survived. There is much absent and much silence where the historian needs evidence and this means that it is often possible to reconstruct only a rather two dimensional and incomplete narrative.

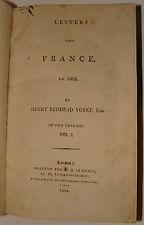

I am writing a book on just such an individual, Henry Redhead Yorke (1771/2-1813), a black political writer and agitator of the French Revolutionary period, little-known today. He became a revolutionary radical in 1792 but then after a spell in prison for his activities he performed a complete volte face and took up an ultra-loyalist Tory position. We know this because he published much political writing and his arrest and trial are well-documented. However, Yorke appears not to have left any personal letters, diaries or memoirs except an epistolary travelogue of a visit to France in 1802. Finding evidence of his personal life required chasing threads through a motley collection of sources with many dead ends and false leads along the way. Some of the questions this research generated illustrate the problems Hanley and Killingray identified.

I am writing a book on just such an individual, Henry Redhead Yorke (1771/2-1813), a black political writer and agitator of the French Revolutionary period, little-known today. He became a revolutionary radical in 1792 but then after a spell in prison for his activities he performed a complete volte face and took up an ultra-loyalist Tory position. We know this because he published much political writing and his arrest and trial are well-documented. However, Yorke appears not to have left any personal letters, diaries or memoirs except an epistolary travelogue of a visit to France in 1802. Finding evidence of his personal life required chasing threads through a motley collection of sources with many dead ends and false leads along the way. Some of the questions this research generated illustrate the problems Hanley and Killingray identified.

Barbuda

The first such question was where did Yorke originate from? After much detective work I discovered that his father was Samuel Redhead an estate manager for the Codrington family and sugar plantation owner in Antigua and his mother was an enslaved woman from Barbuda a poor, barren island, 30 miles north of Antigua. Yorke was born into the slave society on the island and was raised there until he was six. The only white person on the island would have been his visiting father who divided his time between Barbuda and Antigua (where he had children with another enslaved woman).

Yorke was, then, an illegitimate Creole[1] and brought up with two other illegitimate children of his parents and probably a few children of either of them, all of mixed African and European descent. Samuel Redhead never married Yorke’s mother, he had been married years before to a white woman from a wealthy and established Antiguan family of English descent. They had five children before she died in 1742. Yorke was not Henry Redhead’s surname but one he attempted to adopt in 1792, the reason for this remains a mystery. He ended up being called ‘Redhead’ or ‘Yorke’, or Redhead Yorke, not quite one thing or another – the motif of his life.

Yorke was, then, an illegitimate Creole[1] and brought up with two other illegitimate children of his parents and probably a few children of either of them, all of mixed African and European descent. Samuel Redhead never married Yorke’s mother, he had been married years before to a white woman from a wealthy and established Antiguan family of English descent. They had five children before she died in 1742. Yorke was not Henry Redhead’s surname but one he attempted to adopt in 1792, the reason for this remains a mystery. He ended up being called ‘Redhead’ or ‘Yorke’, or Redhead Yorke, not quite one thing or another – the motif of his life.

So another question arises about parentage; was Samuel Redhead Yorke’s father? Yorke’s eldest step-brother was thirty-five when he was born and his father was sixty-nine and described in the sources as, ‘enfeebled’, shortly after Yorke’s birth. In his will Redhead left legacies to his illegitimate Barbudan children but referred to Yorke and his brother as ‘my natural or reputed sons’. This seems to suggest uncertainty as to paternity but it was common at the time to identify the offspring of planters and enslaved women in this way.

Perhaps Henry’s real father was a Yorke, but there is no evidence of this. Samuel Redhead did take Yorke to England aged six to be educated as a gentleman which presumably he paid for. This certainly implies paternity, but contemporary letters suggest that Yorke’s mother made false claims as to the paternity of her children and that it was she who wanted her children to be educated in England. Unfortunately, we have no records from either her or Redhead to clarify the position.

Was Yorke free? Samuel Redhead bought the freedom of Henry’s mother from her owner, Sir William Codrington, in 1771 and that should mean Henry was born free. But the rules about what emancipation actually meant in the West Indies at that time are unclear and vary from colony to colony. According to the contemporary writer, Bryan Edwards, manumission did not mean a complete or immediate status change to a free citizen with all the rights that might endow and certainly not to first generation offspring of manumitted enslaved people. All the inhabitants of Barbuda were enslaved except managers such as Redhead, and there was no way to make a living in such a slave economy. So on Barbuda, Yorke would have lived as more or less an enslaved person, but in England, within the Gentry milieu he was situated, it would have been assumed he was free.

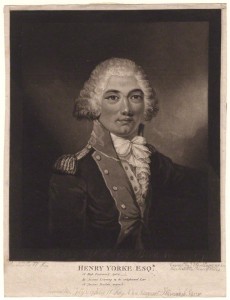

Henry Redhead Yorke by James Ward © National Portrait Gallery, London

Was he ‘black’? Yorke was of ‘mixed race’[2], but does that class him as ‘black’ in terms of black history? I presume so but how different was the ‘mixed race’ experience from the ‘black’ African experience in Britain? Determining Yorke’s skin colour was not easy due to the lack of photography in his lifetime. He did not mention it in his writings and was described by contemporaries as ‘a mulatto’, a ‘half caste’, and ‘of West Indian origin’. Two mezzotints of Yorke survive and in both he appears to have a dark skin tone. A curator at the National Portrait Gallery has confirmed that the mezzotints reflect contemporary representations of ‘mixed race’ as far as can be determined from such old black and white images.

The final question for now, then, is who was Henry Redhead Yorke? Someone committed to politics, albeit changeable politics, but working out his identity and his sense of self, is much more difficult. As an illegitimate ‘English’ gentleman of mixed African and European descent originally from a slave society in the West Indies, he clearly he had a ‘multi-layered’, ‘hybrid’ identity as historians might describe it. Only fragments as to his personal views and life can be gleaned from his published writings and these are difficult to piece together. Thus, as with many such individuals only an incomplete history of Yorke can be compiled, his story is one of absence as much as presence. Yet he gained a voice, asserted agency and made his mark on the society within which he lived.

I would argue that such micro histories of little known individuals are important. They may not alone provide conclusive answers to the big historical questions but they contribute to our understanding of the lives of ordinary people; those of excluded or low status, the poor, women, and ethnic minorities. Moreover, in developing the histories of political, cultural or social groups and movements in the past historians need, at least in part, to explore the individual histories of those involved. This may seem obvious but it is not actually what most historians do, or have done in the past as the work of E.P. Thompson illustrates. To return to the original point perhaps we need now to expand our exploration of black history in Britain, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to incorporate those who were, black, or of ‘mixed race’, enslaved, or not, in order to find a more accurate representation of the complexities of British culture and society.

[1] During the time in question, in the British context, this word was used to describe a person born in the Caribbean regardless of ethnicity. However, it had other meanings in other regions and at other times, most commonly to indicate mixed orgins.

[2] This term is being used by the author as the discussion refers to modern debates concerning ‘mixed race’ identity; it is still considered an official ethnicity category by the UK Office for National Statistics. However, the term is contested by some as it is linked to a history of thinking that implies it is possible to have pure ‘races’.